Patent Corner

Blog

By Damon Kali

•

19 Oct, 2020

Getting your invention to market is a long process full of pitfalls for the unwary. Every step of the way requires thoughtful action or inaction as the case may be. In this post, I'll take a look at some of the things that trip people up when trying to get a patent. The phrase, "Bars to Patenting," sounds like a Spring break mantra used as an excuse to get busy drinking, but actually refers to actions or inactions that prohibit a person from getting a U.S. Non-Provisional Patent. What follows is a non-exhaustive list of things to do... or not to do to preserve your right to file a patent application. I'll divide the list into actions and inactions. Let's get started! Actions Offering to Sell the Invention : There are two keys here. One is that the offer to sell must be an offer to sell the invention. This is not to be confused with offering to license the invention. See below for clarification. The second key is that this action comes with a one-year timer - a bar date. That is, after you offer to sell the invention, you have one-year to file an application on the corresponding invention. Let's say you are in your garage working on your invention and your nosey neighbor walks in to say hello. Nosey neighbor asks what you're working on and you explain your incredible idea. When you're done, you say, "Would you like to buy one when I've got it done?" That's an offer to sell. Often times, an offer to sell comes when actively pitching your invention, but it can be relatively informal as well. You might counter that this was not an actual offer to sell, but just talk and no intention to actually sell was made. That's the way lawyers think and you should proceed very cautiously. Selling the Invention: The same keys as an offer to sell are applicable here. The sale must be of the invention and the sale triggers the one-year timer. Remember, the sale need not be between businesses or even invoiced. You may sell your invention at your local farmer's market or even at your neighborhood yard sale. Both count a sale. Tick tock. Publishing the Invention: Publishing means making the invention public. How public? Well, one inventor had a master's thesis describing his invention that was referenced in one library's card catalog where the thesis was stored. That library was not the Library of Congress, but a small college library in the middle of nowhere. If you're from that place, you have my sincere apologies for that remark. The important take home lesson is that the availability of that thesis, however obscure, counted as a publication for purposes of barring the patent. Don't throw your invention up on YouTube and expect it won't be counted as a publication. Importantly, this action comes with two timers. The first is the one-year to file timer once a publication has been made. The second is the absolute bar to a PCT application with publication. For the second, that means that the moment you publish your invention, if you do not have a priority application in place, you lose your ability to file a PCT application. I'll discuss PCT applications in another blog post. Here's another important point - it doesn't matter who publishes the invention. Let's get back to nosey neighbor. Later in the day, when nosey neighbor is thinking about your invention, nosey neighbor decides to help you out by posting a vlog on Vimeo extolling your brilliance and the virtues of your invention. Oops. That counts as a publication. Here's an even more obscure example. Let's say you draw up a sell sheet, but are not satisfied with how it turned out. The sell sheet explains the invention and how it works. You toss the sell sheet into the trash. The next day, which happens to be trash day, the trash man tips your trash can over in the street spilling your trash that includes your sell sheet. As fate would have it, a gust of wind grabs your sell sheet and carries it two blocks away where it alights on the windshield of a traveling salesman who is captivated by the idea and, in his search for the inventor, posts a the sell sheet on Craig's List to try and find you. Oops. Publication. Be careful. Inactions Failure to File an Application within a Specified Time Frame : If you've read this far, you know you have a one-year time frame to file and, in some cases, must file before the action has taken place. These timers are inviolable and cannot be recovered. However, if you find yourself in the predicament of having missed a bar date, there are some remedial steps that may be taken. For example, you may have significant improvements that may be patentable and are not subject to the actions described above. At this point, competent legal counsel is the way to go. Failure to File an Application at All : It seems axiomatic that if you don't file an Application then you will be barred from getting a patent. OK. I get that. However, something to consider is that the U.S. is a first to file jurisdiction. If you don't file your application and someone else files an invention the same or significantly similar to yours that they developed independently, then you will likely lose the rights in your invention. It's a bit more nuanced than that, but we're establishing general rules here not attempting to make patent attorneys out of the reader. The important thing is that if you don't file, you don't get to complain if someone else does and makes a gazillion bucks. Allowed Activities Offer to License under NDA : In contrast to offering to sell the invention, offering to license is a different beast. First of all, licensing is not selling the invention, rather, it is selling the right to exploit the invention. Second, this is a statutory carveout. That means, Congress says so, so it's OK. The same publication rules apply as above, so be careful with copies of your sell sheet or other marketing/pitching materials. Disclosure under NDA : This doesn't avoid publication pitfalls discussed above, but it does give you some recourse to go after the person to whom you disclosed your invention if they should intentionally or inadvertently publish your invention. An NDA is a contract and your remedy will be in contract, not intellectual property, so keep that in mind. Refiling a PPA : I'm often asked if an inventor can refile a PPA. The answer is unequivocally, Yes, BUT. The "but" part is the part that I like best because it means my professional career is secure. You can refile a PPA. But the question is will that PPA be valid. Generally, you file a PPA, then one-year later you file an NPA claiming priority to the PPA. If you don't do that, you lose the priority date. That's the typical case. However, what happens if you file a PPA and do nothing. Then two-years later, having no bar dates, you file a PPA again. Valid? Yes. You've lost your original priority date, but you have a new one that is perfectly fine. What happens if you file the PPA, then publish? Then the one-year timer kicks in and you will lose your ability to patent forever if you don't file an NPA either within PPA time period or the one-year time period. Whew. One more example. What if, using the previous example, you don't file the NPA within the time period and you've lost your right to patent - Can you refile the PPA? Yes, you can. But it will not be valid and you cannot represent that you have a valid PPA. If you do, that's fraud and that's no good. I think that' s enough for now. Remember, your actions or inactions can significantly impact your future patenting prospects. Keep Inventing and Stay Safe!

By Damon Kali

•

10 Sep, 2020

In previous post, I discussed the differences between an NPA and a PPA. Design Patent Applications (DPA) are very different. I'll explore some of the differences between the NPA and the DPA and perhaps add more abbreviations to delight and confuse. In general, I like tables, so let's start there:

By Damon Kali

•

09 Mar, 2020

In previous post I stated that there are only two requirements for a Provisional Patent Application (PPA). Here they are again: Fees Enablement Fees are easy. Go to the USPTO fee page here . Scroll down the list to the row entitled, "Provisional application filing fee." Look across to the row to find your fee. I think it's probably important to distinguish between the several entities listed. There's Fee, Small Entity Fee, and Micro Entity Fee. If you're an individual or a small company, you are probably not a Large Entity (that's the column labeled "Fee"). For large think, IBM or Apple. If you are not a Large Entity, then you are a Small Entity. If you are a Small Entity, you may also be a Micro Entity. If that doesn't confuse you, then you're probably a Smart Entity. Most people are Small Entities. You may be a Micro Entity if you qualify. Here are the qualifications: Qualify as a USPTO-defined small entity. Not be named on more than four previously filed applications.* Not have a gross income more than three times the median household income in the previous year from when the fee(s) is paid. ( Here is that number) Not be under an obligation to assign, grant, or convey a license or other ownership to another entity that does not meet the same income requirements as the inventor. * The micro-entity definition states that applicants are not considered to be named on a previously filed application if he or she has assigned, or is obligated to assign, ownership rights as a result of previous employment. Applications filed in another country, provisional applications, or international applications for which the basic national fee was not paid do not count as previously filed application. The definition also includes applicants who are employed by an institute of higher education and have assigned, or are obligated to assign, ownership to that institute of higher education. I was wrong. Fees are not easy. Like everything at the USPTO, there are rules and exceptions to make the knees buckle. When in doubt, contact a legal professional. Enablement is easy. Just tell it like it is. Here's a great example of how it's done from the gospel spiritual song, "Dem Bones." Verse 1 Toe bone connected to the foot bone Foot bone connected to the heel bone Heel bone connected to the ankle bone Ankle bone connected to the shin bone Shin bone connected to the knee bone Knee bone connected to the thigh bone Thigh bone connected to the hip bone Hip bone connected to the back bone Back bone connected to the shoulder bone Shoulder bone connected to the neck bone Neck bone connected to the head bone Now hear the word of the Lord. If you can keep that verse in your mind while you disclose your invention, you'll have a great start. Unfortunately, by the time you finish writing, that tune will be indelibly etched into your mind resulting in random humming of the tune. Here's a good way to start writing your PPA: Take several pictures of your invention and print them out. Show the pictures to a friend who is savvy about the kind of invention you have. Ask them if, after looking at the pictures, they could make your invention. If the answer is yes, go on. If the answer is no, take more pictures and repeat 1-3. Once you have enough pictures to tell your story, label each part with a number directly on each picture. Write at least one sentence for each part of each picture. Here's how that might look... Picture 1 illustrates a side view of the invention. Base 100 is manufactured from a rigid material such as a metal or polymeric material. Base 100 supports arm 102. As shown, arm 102 is pivotally coupled with base 100 at one end. The pivotal connection allows arm 102 to move through an arc of approximately 180 degrees. And so on... Picture 2 illustrates a front view of the invention. As shown base 200 has a rectangular profile however, any profile may be utilized without departing from embodiments disclosed herein. And so on... A couple of points: Note that I'm starting at a logical point - the base. You can start at the top if it makes more sense. The important point is that you proceed logically from one point to the next... thigh bone connected to the... Don't jump around. Just name the parts in order and describe what they are and what they do. Note the numbering. For Picture 1, the parts start at 100. Likewise, for Picture 2, numbering starts at 200. I recommend this convention as it will make it easier to always know where you are in the description. It also makes it easier to edit. Note that I described location as well as function. I did not describe a specific part like a ball joint, a heim joint, or some other known pivoting connector. It's not intuitive, but try to generalize your parts and functions. 7. H ave someone you trust read your description to determine whether it is understandable. 8. Repeat 6 and 7 as necessary. Congratulations, you have the basis for a solid PPA. You've shown every view of your invention in pictures and described every part in every picture. That is enablement because that allows one skilled in the art to make and use your invention. See, that was easy wasn't it?

By Damon Kali

•

03 Feb, 2020

By now we've established that a) you probably shouldn't write your own patent and b) that the process is expensive. Therefore, it behooves an inventor to think carefully about choosing a patent attorney to represent their interests for the foreseeable future. To start with, remember that you, as an inventor, will likely be with your patent attorney for an extended period of time. Since the process is so long and complicated, selecting someone you can get along with is very important. In my mind, whether you can work with someone for an extended period boils down to relationship and communication. Whether they can get the work done boils down to education and experience. So, with that in mind, let's start. #1: Get a Referral I think the single best way to meet a good patent attorney is to get a referral from a friend or trusted source. Nothing is better than knowing someone who is satisfied with the work from a competent attorney. How do you do this? Talk to your friends and see if anyone knows a "guy," or who knows a guy who knows a guy. Another way is to go to an inventor's group in your area. Inventor groups are everywhere and most can be easily found with a search engine. You can also attend a hardware show and go find the inventor section. In Las Vegas, the annual hardware show generally has a couple of thousand square feet set aside for inventors with new products. Go meet some inventors. Still another way is with an online referral source like Avvo , Martindale , or Legal Match . Whichever way you go, you should plan on speaking with a few different attorneys before you make your final decision. #2: Check Credentials Patent attorneys must hold a license in the states in which they practice as well as a license to practice before the USPTO. The bar association for each state will let you know whether the attorney's license is current and whether there are any disciplinary actions against the attorney. The same goes for the USPTO. This is an easy and necessary step. I have had more than one unhappy inventor approach me to figure out why their Application is floundering before the USPTO only to find out their attorney is no longer licensed to practice law. Oops. #3: Interview the Attorney Here are some questions you might ask... - What is your area of expertise? - What is your technical degree in? - Where did you go to school? - How long have you been practicing? - What kind of firms have you worked for? - What size of client do you typically have? - Who will be working on my matter? - How will I be billed? Hourly? By the job? - How do you bill for phone calls? Email? Postage? - Is a retainer required? How does it work? - Do you really think that Wile E. Coyote was treated fairly by Bugs? That last question was to make sure you're still paying attention. In interviewing a patent attorney, one of the most important things to pay attention to is whether or not you're communicating with each other. By that I mean, are you being heard and understood and are you understanding what you're hearing. If you can't communicate with the attorney, then you probably will not have a good experience. This speaks not to the competence of the attorney, rather to whether two individuals can express themselves to one another. Keep in mind that patent attorneys, as a group, are not always communicative. It is the nature of the work that draws a particular type of individual. Fortunately, inventors and patent attorneys share many of the same attributes as many patent attorneys are also inventors. So, there is good likelihood that you can find an attorney that speaks your language. #4: Get a Sample You can feel free to give your potential attorney an idea of what you've invented. Nothing is more frustrating to me than an inventor who wants information about patenting their invention, but won't tell me what it is. Attorneys are under obligation to keep your information confidential. That said, let your potential attorney know what you've got and ask if they've written anything in that area of technology that you can review. An allowed patent would be best. If they don't have anything directly related, don't fret. The point of this exercise is to see whether you can read and understand what is written. A patent should be written in clear and concise language. If you cannot understand what the invention is after reading what the attorney has written, then it's unlikely you'll be happy with the end product. In the final analysis, a patent is a story and that story should be decipherable to other human beings. One thing to avoid in your patent reading is the claims. Unless you've read a lot of claims, you will likely be a little mystified. Claim writing is an art form all its own. Read the body of the Specification and look at the drawings and ask yourself, "If my story were written by this person, would I be happy?" If not, move on. #5: Take your Time If you don't find the right person the first few times, don't get discouraged. Keep looking around until you're comfortable. Don't let anyone pressure you. One red flag I have is an attorney attempting to scare you into filing something immediately or losing your invention forever. Unless you have an immediate deadline or bar to patenting, you should take enough time to find someone who is a good fit for you. How long? Long enough to get it right!

By Damon Kali

•

27 Jan, 2020

A communication from the USPTO can be a daunting thing. One such communication is an Office Action, which is the formalized way that the USPTO tells the Applicant all the reasons why their invention doesn't merit an allowed patent. Rarely are claims for an invention allowed as presented. Usually, all claims are rejected for a variety of reasons. Sometimes the rejections are merited and sometimes not. However, in all cases, an effective response must be made in order to advance the Application and avoid abandonment. There is a dizzying array of information that must be processed and addressed in order to effectively respond to an Office Action. If you miss any of the rejections or objections made in an Office Action, you may receive a Notice of Non-Compliant Response, which will require you to address whatever you may have missed. Thus, it behooves you to get some good advice when responding to an Office Action. In this post, I'll cover the main statutory rejections that are most commonly presented. Buckle up campers. What follows is not for the faint of heart or the sleepy. Section 101 A 101 rejection is a subject matter rejection. Here is the list of eligible subject matter: - any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter And here is the list of non-eligible subject matter: - laws of nature, natural phenomenon, abstract ideas, abstract intellectual concepts, mental processes, and mathematical algorithms What does this mean for the average inventor? Mostly, not a lot. The average inventor, by my definition, is a person who tinkers around with things in the garage and comes up with an invention to fix something. Almost invariably, the result of the tinkering is a real, tangible "thing." Because it's real and tangible, it will likely be in the eligible list and avoid the non-eligible list. Just for fun, let's consider non-eligible items. An invention that adds three numbers together and then subtracts the date would be considered non-eligible because it is an algorithm. Lots of software is based on algorithms. That's why software patents must include some integration of hardware to become eligible. Another non-eligible item would be the "discovery" of some naturally occurring chemical element (Think periodic table of elements). Naturally elements are a natural phenomenon, so no love there. However, a method for extracting the new element may be patentable as a method. A law of nature, such as gravity, is not patentable - I'm still waiting on an anti-gravity bed which would most certainly be patentable. Still another non-eligible item would be a perpetual motion machine. If you have one of those, don't bother trying to patent it - it doesn't work anyway. Mostly, the 101 requirement is easily met by most inventive work. Section 102 A 102 rejection is a novelty rejection based on a single reference. Suppose you have attempted to patent a bowling ball. A single reference showing a bowling ball would anticipate your invention and thus your application would be rejected. Overcoming a 102 rejection is done by showing the structural differences between the invention and the cited reference. Let's look at the bowling ball again. Suppose your bowling ball, instead of two finger holes and a thumb hole had two thumb holes to accommodate the bowler who is born with two prehensile thumbs. A little known fact is that some dragons have two thumbs.* Thus, your invention allows dragons with two thumbs to bowl with aplomb. (For those rolling your eyes, stop that!) In order to overcome the 102 rejection, the Applicant would argue that the fourth hole's placement is not disclosed by the cited reference. What happens when the invention is used for another purpose? Let's say the Applicant is using the bowling ball as a paperweight and claims a paperweight that is in the shape of a sphere and has two finger holes and a thumb hole for easily moving the paperweight. In this case, there is no structural difference, but there is a functional difference. Result? No bueno. Functional use and language will not get you very far unless that language clearly differentiates and narrows the invention. In this case, you might try a method claim to get around the cited reference. Unfortunately, you may still fail based on obviousness which we'll get to shortly. What about a miniaturized version of the bowling ball? Nope, not going to happen if the structures are the same but differently sized. Generally speaking, sizing will not get you around a 102 rejection. Section 103 A 103 rejection is an obviousness type rejection and is made up from a combination of references. Going back to the bowling ball paperweight. Let's say that you decide to flatten a portion of the bowling ball for the paperweight. This flattened portion keeps the bowling ball from rolling off your desk and smashing your toes. A 102 rejection based on a bowling ball reference would not alone support a rejection because the flattened portion is a structural difference between your invention and the bowling ball reference. A 103 rejection would present the bowling ball reference in addition to a separate reference of a ball having a flattened portion. That combination would render your invention obvious in light of the two references. Here's the fun part about 103 rejections: a) The references need not be from the same art; and b) Any number of references may be used to reject. What does that mean? For a) that means the Examiner can pull from any source. In our example, the flattened ball portion need not be related to a paperweight. It could be any flattened ball from anywhere. For example, here is a search of newel post with a ball cap. A newel post is a staircase railing piece. If you scroll down the page, you'll certainly find a sphere with a flat portion. What does a newel post have to do with paperweights? Absolutely nothing. Fun huh? For b) that means the Examiner can piece together any number of references to come up with your invention. Let's leave the bowling ball for now as I think we've exhausted that example. Let's suppose you've been raking leaves and you think, "Wouldn't it be nice if I had a broom, a rake, and a pointy stick in the same device?" So, you invent a device with a rake on one end, a broom on the other, with the rake removable to reveal a pointy stick. I bet you've never seen that at the hardware store. Unfortunately, your invention would likely be rejected on the combination of a rake reference, a broom reference, and a pointy stick reference. Overcoming the combination includes arguing that there are different structures not covered by the references, that there is some synergistic or unexpected result, or that there is no motivation to combine the references. These are nuanced arguments and should be made by an experienced practitioner. Section 112 112 rejections generally speak to problems in claiming the invention. Claiming is a very formal and structured language that must be observed. To avoid a 112 rejection, claims must be clear, supported, and have correct antecedent basis. Generally speaking, 112 rejections are fairly easy to remedy. Those are the big four. Overcome those and you're on your way to an allowed application and a full night of sleep. Happy Inventing! *I don't know if dragons have two thumbs or not, but since they are fictional I believe I can take some liberties...

By Damon Kali

•

23 Dec, 2019

If you are well-acquainted with patent law, the terms Provisional Patent Application and Non-Provisional Patent Application roll right off the tongue. For those not as well-versed, here's a little primer to help you sort out the differences. I'm going to unwind these by topic of interest rather than just create a list of attributes. Let's give it a go. Terminology Provisional Patent Application = PPA Non-Provisional Patent Application = NPA Term PPA - one-year NPA - 20 years from filing* * This presumes an Issuance of the NPA. An NPA doesn't actually have a term. Rather, an issued patent has a term. The Application/Examination part of your NPA can be quite long and extended as long as you're willing to pay for continued examination. Formalities PPA - Enablement and Fees. NPA - Lots. Enablement means a person skilled in the art can make and use your invention. No hiding the secret sauce. The NPA has a lot of formalities in both content and structure. If you are thinking of trying to learn all the formalities to write your own NPA... think again. There are pitfalls for the unwary that may result in the loss of your intellectual property. Timeline PPA - After filing there is only the one-year expiry. NPA - After filing it may take 1-4 years for the examination report to be returned. Prosecution of your Application will then likely take a year. If successful, Issuance will be another six months. Protection PPA - You get a priority date for your invention, which means you establish your place in line. If an inventor with the same invention gets in line before you, they win. If you get in line before them, you win. By winning I mean that your application has priority over theirs. NPA - If issued, you get the right to exclude others from making, using, selling, offering for sale, importing, inducing others to infringe, and/or offering a product specially adapted for practice of the invention as claimed. The claims define the boundaries of the invention. This is a good time to draw closer attention to the term "exclude." Your patent rights are rights to keep others from practicing your invention, which is not the same as giving you the right to practice your invention. What? Yes, your issued patent will not give you any rights to make, sell, use, or practice your invention. Why is that, you might ask? It doesn't really matter, that's the way the law is written. I don't say this to be flip. Well, maybe a little flip. There are plenty of scholarly articles that bend over backwards to explain why the law is this way, but really, it is what it is. A better thing to do is give an example to understand how it works. Let's say you've invented a new machine gun. (I'm using a gun example because I know it may stir some second amendment sentiments and get some folks up in arms...!) You file your firearm NPA and, in due course, receive an issued patent. Patent in hand, you start manufacturing and selling your novel firearm. Result... jail. The reason is because your patent did not impart the right to make machine guns. For that you need to consult with the appropriate federal authority to legally manufacture firearms. However, let's say a major licensed firearm manufacturer starts making the firearm claimed in your patent. Result... you have the right to try and stop them from doing that. Mostly that means either suing, working out a deal, or both. Costs PPA - Filing fees are low. NPA - Filing fees three times as much as PPA. The cost question depends on whether you draft your own PPA or not. As a sole inventor, you may wish to draft and file your own PPA. In that case, the costs are about as low as you can get since your time is donated. Getting an attorney to draft your PPA will cause costs to rise. In some cases as much as an NPA depending on how thorough you want to be. Preparation costs for the NPA are quite high. See my post on costs. Hopefully this gives you a better idea of the differences between a PPA and an NPA. There are more differences and, as always, it's good to consult with a professional to address your specific questions. Patent Corner... Out!

By Damon Kali

•

10 Dec, 2019

It costs a lot to get a U.S. Non-Provisional Patent. If you're a sole inventor, you'll probably spend upwards of 15 to 20K from start to finish for a relatively simple invention. If you're lucky enough to be employed by a big company, you won't be out of pocket, but you'll still invest a considerable amount of time and energy getting it done. When all is said and done, it is not for the faint of heart or light of pocket. Here's why. Patent Attorney - I like to tell people that a patent attorney is like the brain surgeon of medicine, which is a not so subtle way of declaring how smart I think I am. The truth is that becoming a patent attorney requires a lot of schooling and expertise. A patent attorney must have both a technical degree as well as a law degree. They must not only pass their state bar, but the patent bar as well. Because patent law is a specialty, engaging a patent attorney can be an expensive proposition. In addition, patent law requires support staff to track and process the various filings. When filing a patent application, you'll likely be hearing from a paralegal as well as administrative staff during the process. It's not a one-person show. Longevity of the Document - an issued patent has a term that lasts 20 years from filing. There are notably few legal documents as complicated as a patent that are expected to survive for 20 years. This means that the patent must be drafted very carefully and thoughtfully, which is not to say that all patents are drafted carefully and thoughtfully. There are sources that claim to draft a patent for under 2000.00 USD. My response almost always starts with a story about a little car known as the Yugo . Process Time - It typically takes two to four years to get a Non-Provisional Patent Application through the process . That's a long time. During that time, a lot can happen... or not happen. In any event, the patent attorney must track the process the entire time or risk incurring significant penalties. Which brings us to... Penalties - The patent rules are fairly unforgiving. That's probably not the correct way to state that. A better way would be - The patent rules can be expensive. Let's say you miss a filing deadline. No problem in most cases, a one-month extension fee of 100.00* will overcome the problem. But what if you miss your mark by five months? That's a whopping 1500.00. Or perhaps you forgot to file your 3 1/2 year maintenance fee. No problem, a 1000.00 petition will get you back on track. This kind of accountability requires a high degree of care to manage and, like any good capitalistic venture, gets passed on to the consumer. USPTO Fees - Filing a Non-Provisional Patent Application is about $800.00 in fees to the USPTO. Got more than 20 claims? No problem. $50.00 more per claim. More than three independent claims. No problemo. $230.00 more per independent claim. Is the Examiner not convinced after the first examination that you deserve a patent? Aucun problème. Continue the examination for $650.00 the first time and $950.00 every other time. Got your patent allowed? Congratulations! How about another $500.00? This is a time-consuming and expensive process for good reason. Spending some time in deciding whether you are going to go down this track is a good idea because you're going to be spending a significant amount of your hard earned money if you decide to hop on this train. All aboard! *All fees referenced in this blog are based on 2019 USPTO fees for a small entity. If it's not 2019, the fees have gone up. Large entity fees are double.

By Damon Kali

•

03 Dec, 2019

In a previous post I recommended that an inventor not write their own Non-Provisional Patent Application (NPA). This not the case with a Provisional Patent Application (PPA), which does not require the formalities of an NPA. The PPA is a beast of an entirely different nature. Here are a couple of points to remember about your PPA: A PPA is not a patent. It is an application. This is important because... A PPA does not provide you with patent protection and… A PPA expires 12 months from the time of filing. See the timeline here . A PPA provides a priority date for purposes of filing. A PPA requires enablement. I'm not going to go into further detail on these points here. We'll save that for another day. And now, a few issues that confront inventors when drafting a PPA. 1. Overthinking It Don’t overthink it or psych yourself out. Putting together an effective provisional patent application is simpler than you think. A PPA is, at its core, your story. Think of how you would explain your invention to your mother or spouse - In common English. If you write your PPA that way, you’re most of the way there. One word of caution - Do not, under any circumstances, read a published utility patent to get insight into the process. Doing so will not only ruin your day, but it will create the impression that you must learn a new language to write a patent, which is true, but irrelevant to writing a PPA. Don't let the task overwhelm you. 2. Failing to Enable Your Invention Don't hide the secret sauce. That's the lesson here. You must disclose what your invention is and does with clarity. This is one of the few requirements of a PPA. Here's the test: if someone reads your PPA; understands your invention; and then knows how to make and use your invention - you pass! If not, go back and add more detail. I don't think it's a bad idea to share your description with a trusted friend as a gut check. When in doubt, get competent legal advice. For the hopelessly paranoid, your provisional patent application never becomes public if you don't file a corresponding NPA. There is very little chance that someone might steal your idea if you put it down on paper and file it as a PPA. Reveal everything, hide nothing. 3. Unintentionally Limiting Your Invention Even though there is an enablement requirement, you will want to avoid requiring too much specificity in your PPA. When inventors describe what they have invented, there is a tendency to create unintended limitations. Here are a couple of descriptions: My invention has a base made from aluminum. While it may be true that the base can be made from aluminum, is aluminum the only material suitable for the base? Probably not. More likely aluminum was chosen for other reasons. One of the reasons may be as simple as that is what the inventor had lying around in the garage. The base is made from a rigid material which includes any of: aluminum, steel, a polymeric compound, a composite material, and the like. This example avoids limiting the base material to aluminum and includes other suitable materials that might be used to form the base. One way to avoid this issue is for each element of your invention ask yourself the following questions: Is this the only way to make this? Is this the only material that can be used? Is this the only way to do this? When you limit yourself to a specific material or method, you give others an opportunity to design around your invention. Thinking about other ways things may be done is the way to go. 4. Omitting Illustrations It is common knowledge that a picture is worth a thousand words. I'll write that again. It is common knowledge that a picture is worth a thousand words. If I had a picture, I could have eliminated all those words... Probably. Use illustrations. If you can draw well - draw. If you can't draw - take pictures. Almost anything goes in a PPA. When you take a picture, look at it and describe what it shows. If there is something you can't see, then take another picture of the previously unseen part and describe it. I'm often asked how many drawings or pictures should be present. I used to say, "As many as are required to tell the story." Now I just say, "Six." That's not really the number, but it makes people feel better. Pictures goood. Fire baaad.* 5. Using Inconsistent Terminology It is important to use the same words to describe the same thing the same way. If that last sentence doesn’t make your eyes water, you may want to consider a career in law. For example, it would be a mistake, when referring to a fishing pole, to also call it a fishing stick or a fishing spear at different points in your PPA. You do not want any confusion as to what you have invented. Be very consistent. Don’t hesitate to be repetitive. Various names for your invention might be appropriate in your marketing copy, but it has no place in a PPA. You say potato and I say potato... but at least we're using the same word. Keep it simple and keep it consistent. 6. Using Trade Names and Trademarks Most inventors like to come up with catchy names to call their invention. These names are known as trade names. Trade names are very useful marketing tools, but have no place in a PPA. For example, see if you can tell the difference between the next two descriptive sentences: The invention is the swirly twirly brush that eliminates using Liquid-Plumr (R) for stubborn clogs. The device is a bristle brush attached to a spring to mechanically clear drains therefore eliminating the need for chemical clog removers. The first sentence contains the inventor's trade name for the invention as well as a registered trademark. Unfortunately, the trade names are not adequately descriptive of the invention nor is the use of a trademark sufficiently descriptive. The second sentence gives me a warm fuzzy feeling because it clearly describes the invention. Don't use trade names or trademarks. 7. Using Color There are times when color may have some utility - such as when the use of red causes an involuntary response in an otherwise docile bull to charge and trample anyone within eye sight. Otherwise, don't use color to describe your invention. Color is generally considered an aesthetic attribute as opposed to something that has utility. In my case, I'm wearing a red shirt, purple jacket, gray sweats, and brown socks while writing this post. You may think that is an aesthetic choice. You would be wrong. It is a clever way of getting people to avoid eye contact with me while I'm busy. Leave color for coloring. Hopefully these points will help you draft a better Provisional Patent Application in the future. * This is an obscure reference to the movie "Young Frankenstein."

By Damon Kali

•

20 Nov, 2019

As an inventor, have you ever found yourself thinking there is nothing else left to invent? If you have, you're not alone. Even the most prolific inventors sometimes find themselves stuck. The quote, ""Everything that can be invented has been invented," is generally attributed to Charles Duell, the Commission of Patents from 1898 to 1901. Although this quote has been debunked , the sentiment has certainly been felt by many. Invention is an art form. As an art, inventing requires not just talent, but patience and hard work. So, instead of thinking of an inventor as an obscure and introverted life form bent on tinkering with every device within reach, let's think of an inventor as an artist. I feel better all ready. As an inventor artist myself, here are five things that help me keep the inventive juices flowing: 1. Relax Nothing kills invention more than being busy. This may seem inconsistent particularly given my statement about hard work above. I'm not really referring to hard work though. I'm referring to being busy. It always seemed to me, growing up a baby boomer, that being perpetually busy was not only desirable, but highly regarded by post WWII society. I've since learned that being busy is not the same as being effective. Movement without purpose is just movement. In relaxing, an inventor needs to relax their mind by removing themselves from hustle and bustle. This is often not a tall order for inventors since we know that inventors are generally introverted. However, even an introvert can busy themselves with tasks that have no other purpose than to use up free time. Meditation, although I'm too busy to do it, is often a good way to relax your mind and find a peaceful place. For me, I like to just sit on my porch and look at the trees. When someone asks me what I'm doing I reply, "Leave me alone, I'm busy relaxing." 2. Broaden Your Sights Narrow mindedness is not the same as focus. There is a reason why people who are stuck often remark that, "They are in a rut." They are in a rut because the rut defines their perspective. One of the inventor's great gifts is the ability to focus on a task to the exclusion of everything else. Some might call that obsessive compulsive disorder for which medication is recommended. Naysayers. Focus and obsession are the teeth by which inventors chew up impossible problems. Focus and obsession are also the reasons why inventors often lose interest in everyday tasks. However, the point is not to remove the engine that drives the inventor, but to widen the path traveled. Take time to dabble. When an inventor looks elsewhere, solutions arise that may never have been considered. When I'm solving a problem, I'll start with my basic research - Wikipedia - where else? I have a personal rule that I will open any link that remotely interests me even if it's not related. Because it's a rule, it's not just wandering down the rabbit hole. It's purposeful wandering that, more as not, leads me back to my problem with new ideas. In reviewing my browsing history I think I'm either hopelessly unfocused or brilliant. I'm leaning toward brilliance. 3. Start Making Something Invention is not only a game of the mind, but of the hands. One of the blocks I often experience is when I've conceived of an idea and drawn it up on paper only to find myself hindered by some imagined impediment. Whether the impediment is real or not is often difficult to ascertain because my musing are only fiction at that point. Since I am fortunate to have the space and equipment to tinker, I'll often go out to the garage to try out a few of my ideas. It's an odd phenomenon that occurs when, as I tinker, I find that the solution often miraculously appears once my hands are active. I'm guessing that this is probably a subset of relaxing the mind, but I don't really have the knowledge or expertise to know for certain. I've used this tinkering explanation to justify my collections of tools and equipment. During our last move, I complained to my wife that we needed to get rid of more of her unused stuff to which she replied, "All this stuff is yours." I don't like it when I'm presented with actual facts. 4. Leave it Alone It is said that familiarity breeds contempt. In this case, familiarity, or the relentless pursuit of a solution, often breeds a brick wall. My advice - walk away, leave it be, take a break, give it a rest, or whatever else is needed to create some separation. When inventing, it's important to leave your invention alone to simmer along until the flavors all come together. It may be a good point in this blog to remind the reader that coming up with this many metaphors mixed and otherwise is not easy. I often have two or three projects running simultaneously. Mostly it's because I want to break from an invention and let my mind deal with it in the background. Some people call this procrastination. How wrong they are. Procrastination is leaving something undone because you're avoiding it for some silly reason. This is not that. This is has a good and sensible reason. By having several projects undone, my mind is busy working on solutions that would otherwise confound even the best and brightest. I struggle working hard to not work. 5. Trade Shows This might be classified under "Broaden Your Sights" above with the exception that this occurs in Vegas. Trade shows are a frenzied feeding trough for an inventor. New gadgets, tools, methods, and designs abound at a trade show. The idea when going to a trade show is to simply wander around taking it all in until it's time to go to the Strip. One trade show I highly recommend is the National Hardware Show . I used to go every year when I was actively inventing. Just being around that energy really livened up my desire to invent and got my creative juices flowing. Go to a trade show and get revitalized. To be fair, I have heard that there other attractions in Vegas that may serve as an incentive to leave your cave and venture forth to a trade show, but I have no personal knowledge of that nor can I make any recommendations in that regard. Inventing is and should be fun. Blocks are normal and are less a sign of inability than they are a sign of fatigue. Remove the fatigue and you take the first steps to removing the block.

By Damon Kali

•

11 Nov, 2019

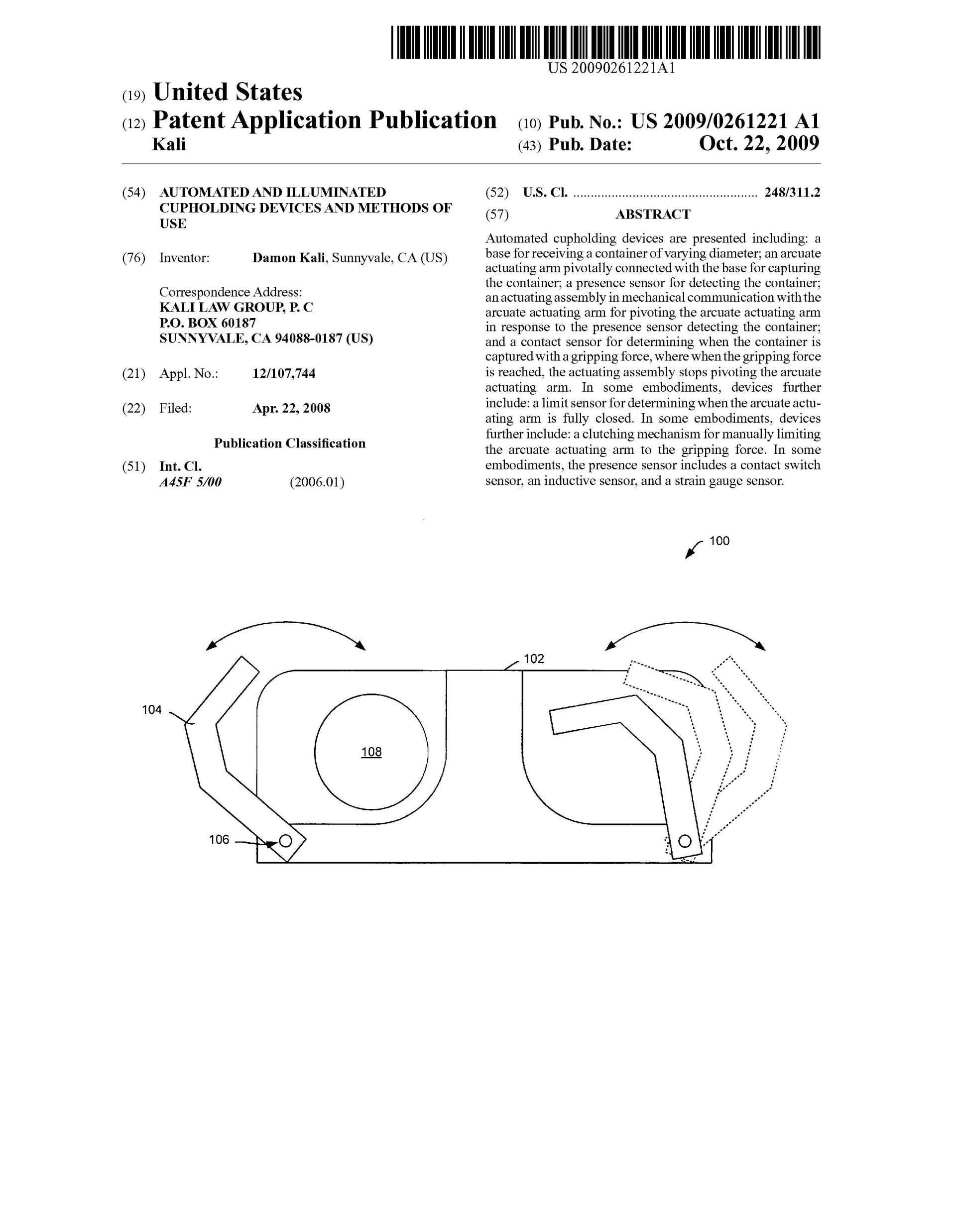

When I was in my mid-thirties, I decided I would write my own patent. I purchased David Pressman's Patent It Yourself and started reading. It's a great resource and you can find a link in my Resources section, but it's a slow read. I'm proud to say I read it cover to cover and decided that I could not, in fact, patent it myself. That is not to say that an inventor, using that book can't patent it themselves... only that I couldn't. I went to law school instead and became a patent attorney. I spent four years after law school wading through the minutiae of patent law and practice before I could write a passable patent. It's hard work learning how to distill a person's invention to points of novelty and reducing that to paper. On the whole, I'd say it's a bad idea for inventors to write their own patent application. I'm not speaking of a Provisional Patent Application (PPA), which will be the topic of another insight discussion, but a Non-Provisional Patent Application (NPA), which is what I will be referring to when I use the term, "patent." Here are four mistakes inventors make when writing their own patent... #1 Misidentifying the Task The purpose of the patent is to protect your right to exclude others from practicing your invention. This is a fundamentally different task that solving a problem, which is what inventors are good at doing. "Well," says the precocious inventor, "Isn't writing a patent kind of like solving a problem?" Yes. And No. And don't be a smart aleck. Yes, it's a problem in the sense that any task could be considered a problem to be solved. And no, it's not the same as inventing a solution to a problem. Think of it this way: An inventor sees a chicken crossing the road and thinks, "That chicken is a dead duck if a car passes by while the chicken is on the road. I'm going to solve that problem." The inventor installs a road switch that triggers the sound of a howling coyote when a car is passing. A chicken crossing the road and hearing the howling coyote will be paralyzed in fear, whereupon the car that triggered the switch will pass by. When no further howling ensues, the chicken will regain composure and proceed safely across the road. This is a cause and effect type of solution approach that inventors are attracted to like Hawaiians to Li Hing*. This self-same inventor then decides to write their own patent application because they did such a good job solving the chicken/road problem . They proceed to write about chickens and roads and the unnecessary deaths caused by unsuspecting chickens crossing dangerous byways. They then describe in excruciating detail how the device works and how well it will sell in the marketplace - entirely focused on chickens crossing roads. This might make a good pitch, but it isn't patent writing. Patents seek to stake out territory encompassed by or anticipated by an invention so no one else can practice that invention or something similar without permission. It's an analysis in exclusion - not cause and effect. What is required is to examine the invention and then ask, "How can I reasonably expand this invention to include more space while assuring that I'm not so expansive that the invention loses all meaning." In this case, the patent application drafter should think about whether this invention has more universal usage - Does it work with all fowl? Must the sound be a howling coyote? What kinds of switching devices might be useful? Is it useful only for road? Can children be scared into eating peas with it? It isn't that the inventor isn't capable of doing this... it's just that they generally don't. Get the task right. #2 Writing Your Own Claims Giles Rich, a former Chief Judge of the Federal Circuit once said, "The name of the game is the claim." The claims are the most important part of the patent application. The claims define the boundaries of the invention. Think of a neighbor dispute when one neighbor builds a fence on the wrong side of a property line. The first action is not to burn down the fence. The first action is to call a surveyor and figure out where the property line is. Then burn down the fence. Claims have a language all their own. Particular words in claims have particular meaning. If you don't know the difference between the terms "comprising" and "consisting of," then you have no business writing a claim. I would put a sample claim here just for illustrative purposes, but that would certainly have undesirable narcoleptic effects. Oh posh. Let's give it a whorl. Here's a claim. Ask yourself if it makes sense... if you can stay awake long enough to get through it. An automated cupholding device comprising: a base for receiving a container of varying diameter; an arcuate actuating arm pivotally connected with the base for capturing the container; a first presence sensor for detecting the container; an actuating assembly in mechanical communication with the arcuate actuating arm for pivoting the arcuate actuating arm in response to the first presence sensor detecting the containe r; and a contact sensor for determining when the container is captured with a gripping force, wherein when the gripping force is reached, the actuating assembly stops pivoting the arcuate actuating arm. That underlined clause really makes my eyes water.... And I wrote that claim! Get some help with the claims. #3 Botching the Formalities A patent application is a highly formalized document. There are rules for everything. Drawings must appear in a specific way; Claims must be presented in a specific way; Sections must be ordered; and on and on and on. If you don't get the formalities correct, you get a notice to correct with no guidance on how to correct. It is at this point in the inventor/author story that I am often contacted. It should not be a surprise that while most issues are generally correctable, some are not. That means you lose your time, your money, and sometimes, your right to a patent. Here's some fun extra credit. Click here to read what the MPEP says a patent application should include and you'll get a taste of why it's incredibly easy to run afoul of the formalities. (I make no apology for that pun) Get it right the first time. #4 Writing a Patent Application Yourself This is the biggest mistake inventors make when writing a patent application themselves. What I realized when I read David Pressman's book was that the process was far too complex for me to navigate on my own. What I discovered upon taking on this profession is that I was right! Your best move, as an inventor, is to get some competent legal advice to draft and prosecute your patent application every step of the way. * No one actually knows what is in Li Hing**, but when I write those words, my mouth waters and I crave anything covered in Li Hing. And I'm Hawaiian. ** I suspect someone actually knows what Li Hing is.

Copyright © All Rights Reserved 2019 Kali Law Group, P.C.

Call us:

+1 408 420 2381

info@kali-law.com

Where to find us:

Portola, CA USA